(n). Clicking on the collection name expands the list of associated accessions and reports the number of objects by accession.

Collections Summary

This document offers a high-level summary of the UM’s collections and accessions. Also addressed are some of the thorny issues surrounding the logging of collections in the UM’s collections database.

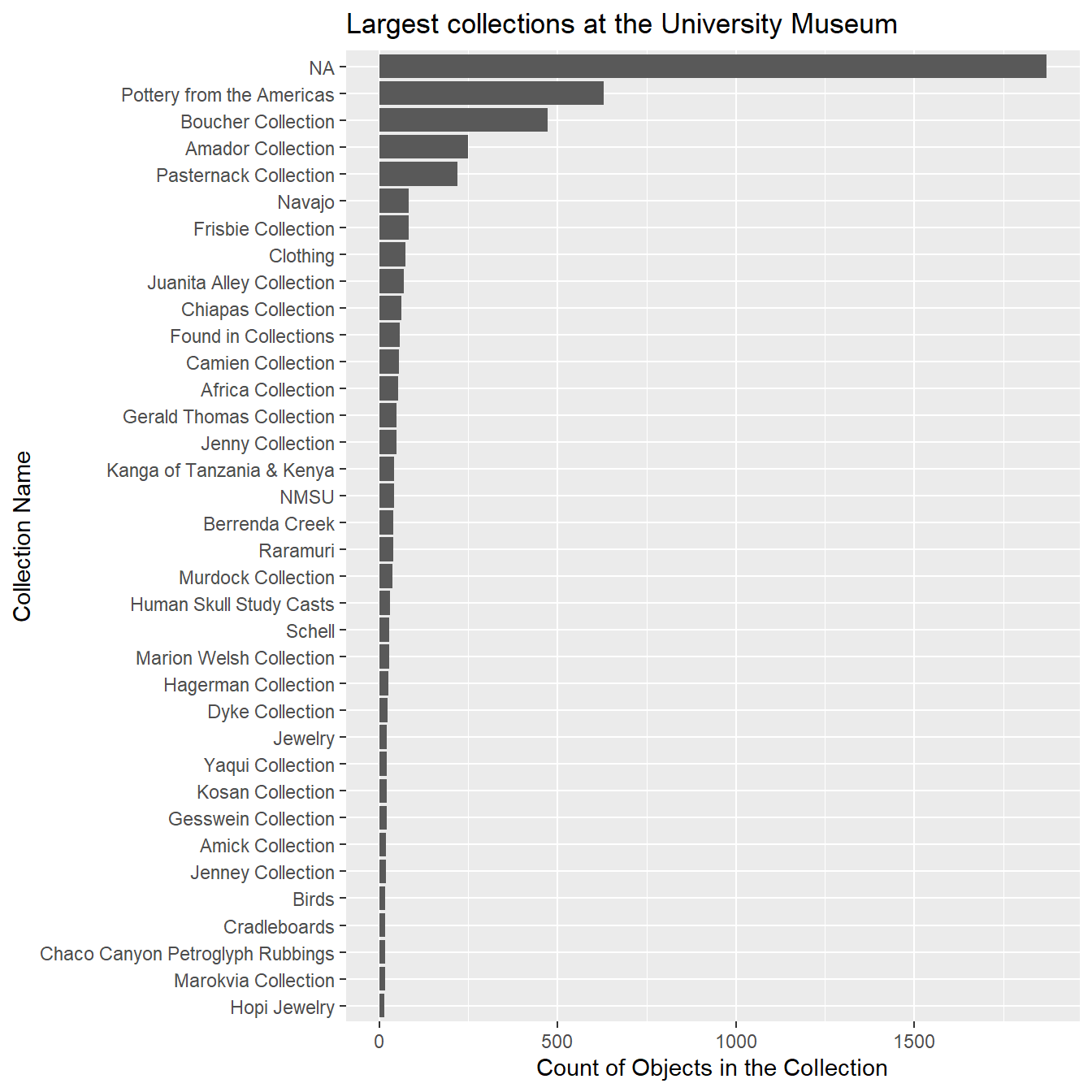

Collections Listed by Number of Objects

As of 2024-06-11 there are 147 named collections in the UM’s holdings. Most of the collections are very small. For example, of the 147 distinct collections 39 (27%) of them are composed of one object while 16 (11%) of them are composed of only two objects. Thus, 38% of the collections are composed of either one or two objects. It likely does not make sense to retain collections composed of so few objects. Only 13 (9%) collections contain more than 50 objects (Figure 1). Table 1 lists the named collections and presents them in descending order with the largest collections listed at the top. To streamline a review of collections, this table is searchable and sortable.

Some Complications with the Collection Field

Many of the (especially smaller) collections are based on:

- ethnic group (i.e. “Navajo” and “Raramui”)

- region (i.e. “Chiapas Collection” and “Africa Collection”)

- or some combination (i.e. “Kanga of Tanzania & Kenya”).

Larger collections are often based around:

- an exhibit that represents multiple ethic groups (“Pottery from the Americas”)

- a single donor and single accession but multiple ethnic groups (“Boucher Collection” and Pasternack Collection”)

- or a single family but multiple accessions (“Amador Collection”)

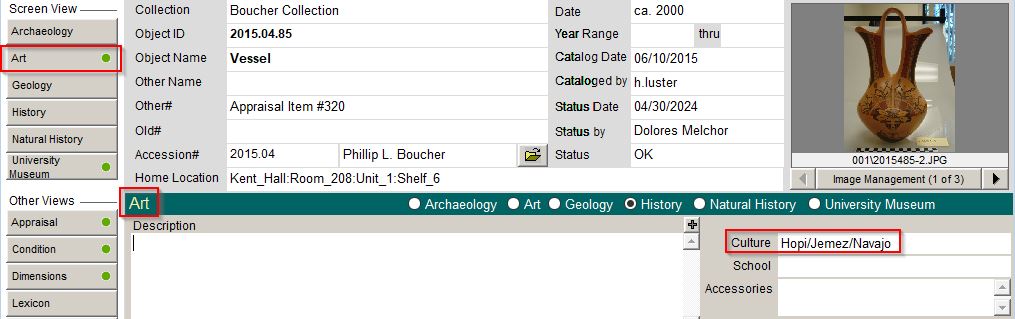

Unfortunately, without the use of clumsy compound list fields which violate the principles of tidy data (Wickham 2014; Wickham and Grolemund 2017; Broman and Woo 2018), PastPerfect does not easily afford assigning objects to more than one collection. Additionally, most collections at the UM are not formally defined and are based on varying criteria which may include culture, culture area, or other attributes (Note 1). Adding to the confusion, within PastPerfect the default Culture field is visible only in the Art tab and may often be formed as an un-tidy compound list field containing more than one value (Figure 2). Except for some older records that need to be updated, the stock Culture field is no longer used at the UM. Instead, Otto customized the database creating a new field Culture (UM) which is stored in PastPerfect’s udf1 field. When Craig encountered the database, information was inconsistently stored across these fields. In some cases, culture information was housed in the stock Culture field but not populated in Culture (UM)/udf1. Similarly, for newer records cultural affiliation information was logged in Culture (UM)/udf1 but not in PastPerfect’s stock Culture field. This made searching the database by culture difficult and error prone. In seeking to systematize and regularize the database while following Otto’s customizations, Craig attempted to migrate culture information out of the Culture field in the Art screen to Culture (UM) (udf1 under the hood) in the University Museum screen. This however, does not solve the matter of having to rely on compound list fields if more than one ethnonym is applied to Culture (UM) nor of situations arising when it makes sene to assign objects to more than one collection.

/ delimiter.

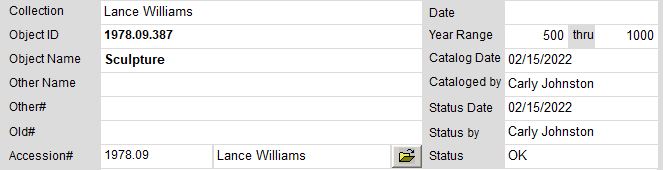

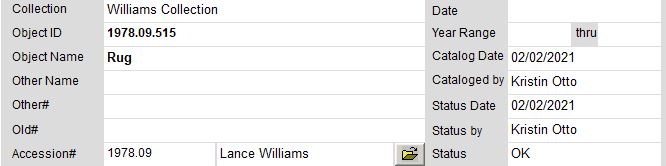

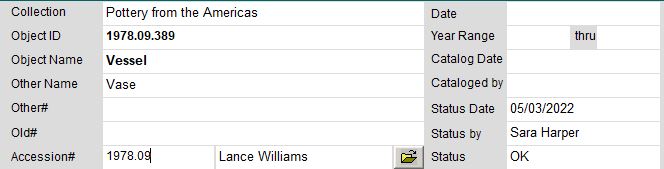

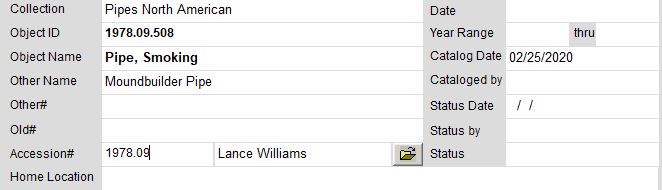

Example 2: Accession 1978.09 and collection complications

Accession 1978.09 is composed of a large number of objects that were donated by Lance Williams. Over time, these objects were variably assigned to the “Lance Williams” collection (Figure 3 (a)), the “Williams Collection” (Figure 3 (b)), “Pottery from the Americas” (Figure 3 (c)), and “Pipes North America” (Figure 3 (d)). Likewise, while in several cases cultural affiliation is known, rarely are objects assigned to a culture group collection even if such a culture group collection (i.e. Navajo) exists (for example Figure 3 (b)).

1978.09 listed as belonging to the “Pottery from the Americas” collection but not part of the “Williams Collection”. This object is identified as having a cultural affiliation of “Ancestral Pueblo” but is not part of the “Southwest”, “New Mexico”, or other potentially relevant collections.

1978.09. Object from this accession were assigned to two collections named for the donor and two collections named for other criteria. In none of these cases are objects assigned to collections that are defined based on culture groups, even when such a collection exists (i.e. “Navajo” collection).

Craig recommends that the UM migrate to a collections management database that permits the assignment of objects to more than one collection and more than one culture group. The system should have the capability of treating either collection or culture as a list rather than a single value.

If it is not possible or practical to move to a collections management database that allows collection and culture fields to be represented as lists, then it makes sense to eliminate collections designations that are based on ethnic groups as this information is logged in Culture (UM) and reserve collections for large groupings of items with something in common and often accumulated through multiple accessions (i.e. Amador Collection or Frisbie Collection).

Accessions

Collections are built on accessions. Therefore, understanding accessions is key to comprehending a museum’s collections. Within PastPerfect, the standard field accesno holds the accession number. Based on this, there are 595 accessions presently logged in PastPerfect (Table 2). The field that holds the source of the accession is a little more difficult to discern. However, Craig suspects that recfrom = “Source” of the accession. Operating from this assumption, it is possible to generate a list of unique accessions logged in PastPerfect and display the associated accession “Source”.

The field recfrom which is “Source” should not be confused with udf3 which is a custom field created by Otto and named “Source”. Craig further notes that many values in the udf3 (Source) field were date related and not source related.

recfrom and udf3 fields which pertain to the accession’s source (Note 2).