flowchart LR RV[Rio Vista] --> A-SH[Seed House] RV --> B-ES[External Storage] A-SH --> KHB[Kent Hall\nBasement] A-SH -.-> B-RD[External Storage\nResearch Drive] B-ES -.-> KHB[Kent Hall\nBasement] B-ES --> B-RD[External Storage\nResearch Drive] KHB --> KH210[Kent Hall 210] KH210 -.-> WH[Wells Hall] B-RD -.-> WH

Collections Management History

This document aims to provide a very broad and general history of collections management at the University Museum. The information is incomplete, but aims to serve as an example of how information can be logged as it comes to light.

Ethnographic and Historic Collections

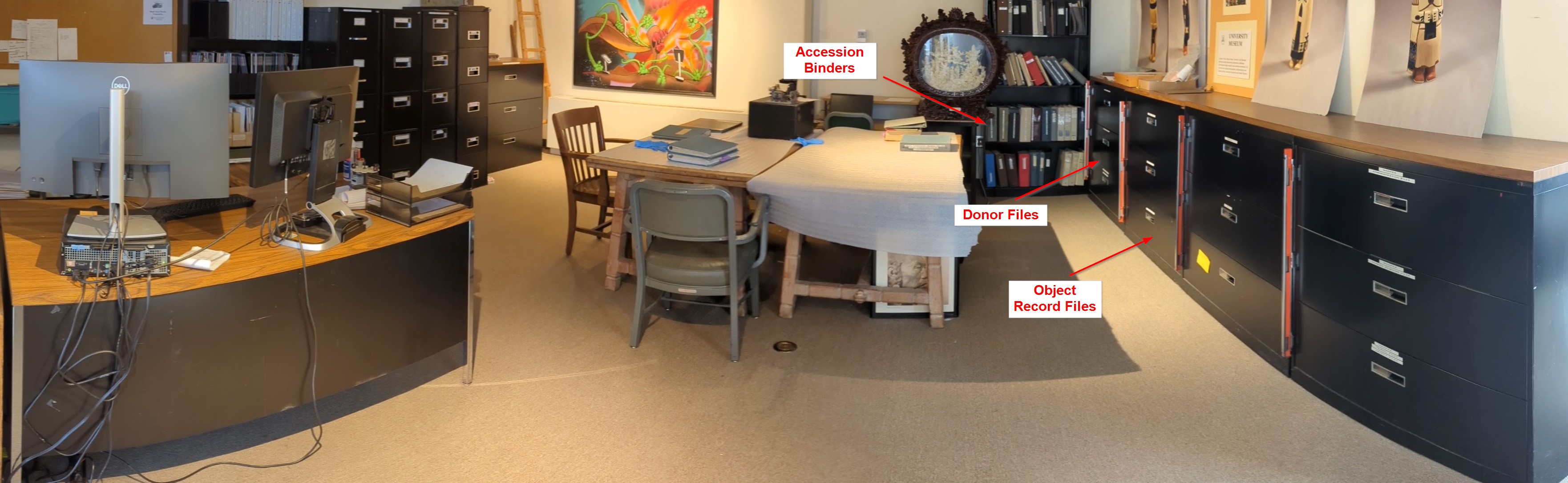

The UM’s permanent collection includes but is not limited to ethnographic (\(n\) ≈ 5000) and historic (\(n\) ≈ 10,000) objects. In fact, the UM’s first major acquisition was the Murdock Collection (1960.01, \(n\) ≈ 238) which is composed of ethnographic objects (Baker 1997, 9), and the second was likely the Amador Collection (1962.08, \(n\) ≈ 600) consisting of historic materials recovered from the basement of from El Jardín (Camien 1962).1 These and other collections are documented in the UM’s paper collection records which are currently located in the southwest corner of Kent Hall (KH) 210 (Figure 1).

Since at least 1998, the UM has used PastPerfect as a collections management database and it continues to use this system today.2 The earliest records in the UM’s database date to 1998–the year PastPerfect was released. Over time more than 100 different users have contributed to the UM’s collections database. The large number of users reflects the changing nature of the UM’s student staff and highlights the institutions role as a teaching museum.

In 2021, Dr. Kristin Otto initiated a project to undertake a systematic inventory of the ethnographic and historic objects in the UM’s permanent collection. To support this effort, Otto applied for and was awarded an Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Grant (IGSM-248937-OMS-21). This project was completed in 2023 (Johnston 2023). Craig published provisional results on the web. Inventory of ethnographic and historic materials is ongoing and subject to revision.

Archaeological Collections

At present, archaeological materials make up the bulk of materials housed at the UM (\(n\) ≈ 170,000). However, Archaeological materials were not part of the UM’s earliest collections.3 Based on a review of museum records, with the exception of a few isolated objects, it appears that archaeological materials did not become a major feature of the UM’s holdings until the later half of the 1970’s seemingly coinciding with the development of cultural resource management (CRM).

The term “cultural resources” was created by the National Park Service in either 1971 or 1972 (Fowler 1982, 1) and cultural resource management (CRM) largely developed after the passage of the Historic Preservation Act of 1966 as well as the Archaeological and Historic Preservation Act of 1974 (Moss-Bennett Act).

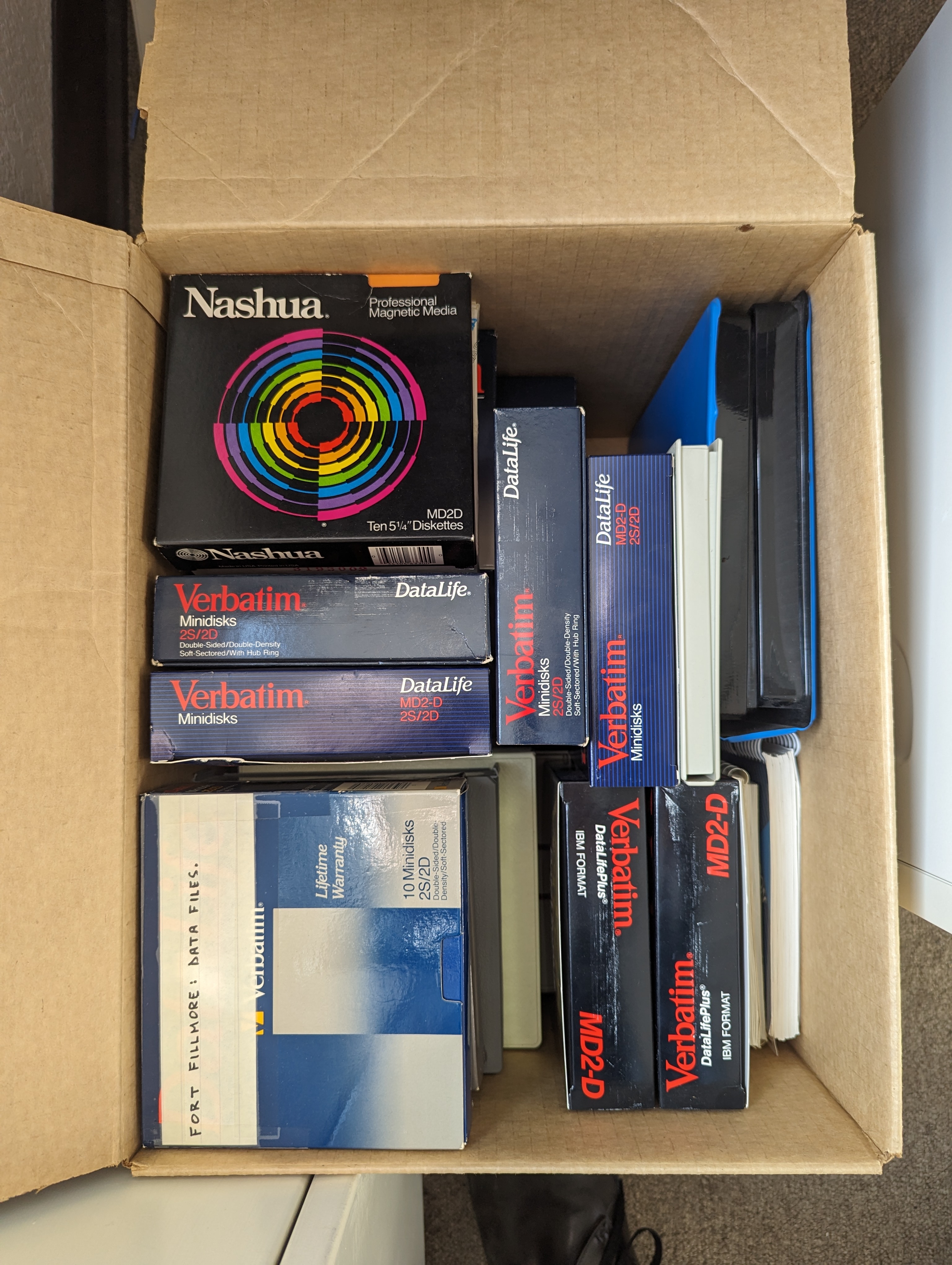

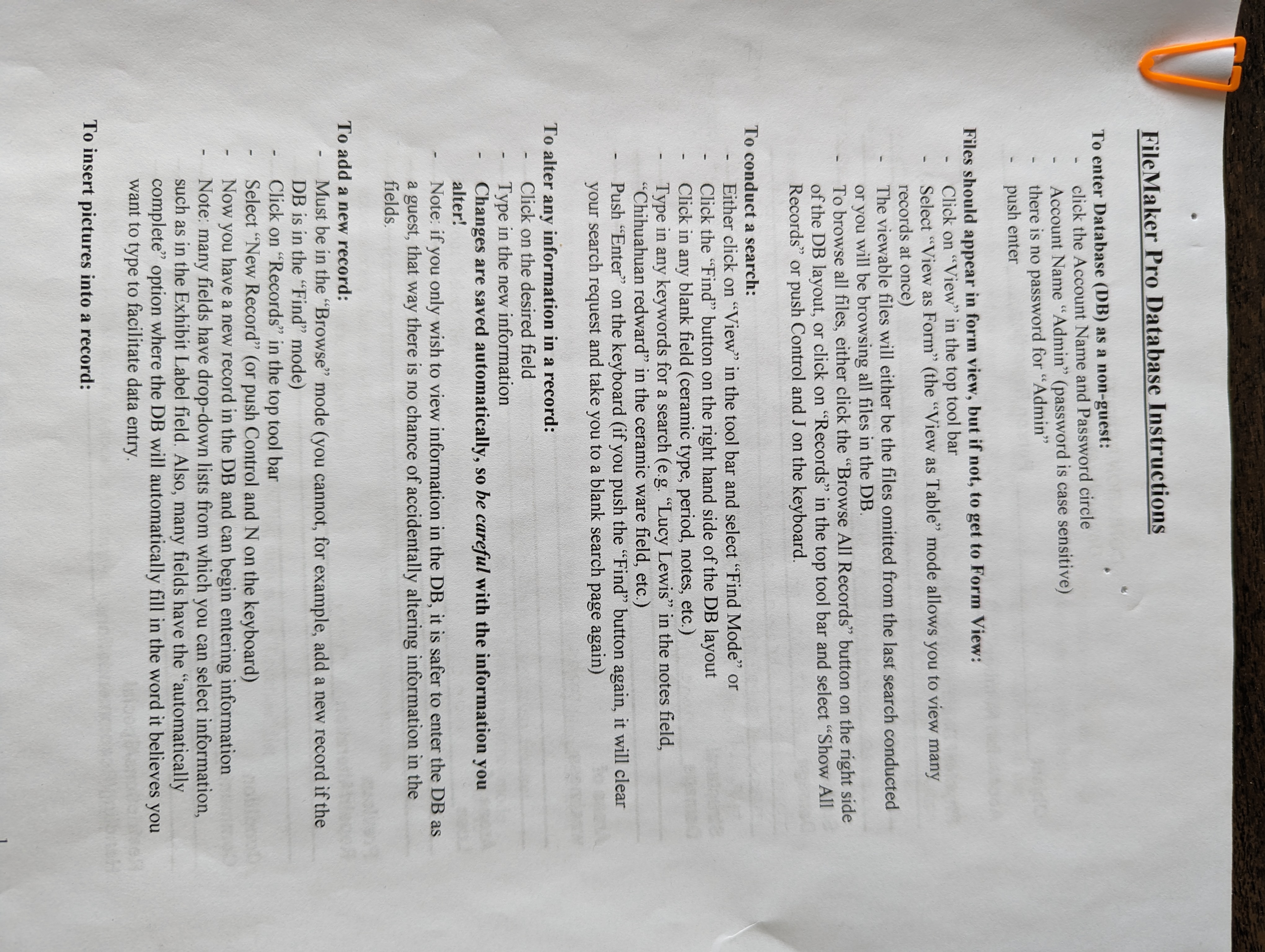

Early on, archaeological collections in the custody of the UM were tracked largely by paper. This likely persisted up to the early 1980’s when consumer grade personal computers became more popular (Figure 2). Both old computer equipment (Figure 2 (a)) and paper documents (Figure 2 (b)) suggest that starting some time in the 1980’s, there was a growing interest in recording collections information on computers (c.f. Grubb 1995). Most of that appears to have taken the form of logging information into spreadsheets.

Before Craig began as Interim Director in 2023, archaeological collections housed at the UM were not systematically tracked in the museums collection management database (PastPerfect). Instead, it appeared that archaeological collections were tracked through paper records and a series of spreadsheets that lacked version control.4 Paper is the most reliable storage media, but it is difficult to index and access information logged in paper media.

Unfortunately, while spreadsheets are indispensable information management tools they are ill suited for many of the fundamental kinds of information that needs to be tracked in a museum setting (Figure 3). Two examples would be object physical location and current condition. Attributes like physical location and current condition change over time, and it is valuable to retain a history of prior observations with the object record. This involves a relationship between one object and many states, also known as a one-to-many relationship. The Museum Registration Manual notes that historically, museums tracked this information with paper Location Files (Simmons and Kiser 2020, 34.19–21). This information can be tracked with a spreadsheet, but organizing a large number of digital files quickly becomes onerous which again points to binding these arrays into an integrated database.

The complexities of object movement are illustrated by an example from the Rio Vista collection. Much of this collection’s early movement history happened concurrent with the beginnings of database theory in 1970 (Codd 1970) and the development of commercial databases by 1976 (Staff 2002). However, object movement does not appear to have been tracked on paper, by spreadsheet, or in emerging database technologies. The Rio Vista collection came into the UM in 1973 (Mayo 1994, 16–17) and moved over time (Figure 4). Objects were initially stored in the Seed House and in external storage. Around 1980-81, objects were transferred to Kent Hall and storage units on Research Drive. It is unclear what parts of the collection went to each location. Within Kent Hall, the Rio Vista material was initially stored in the basement. At some point, Rio Vista materials in Kent Hall were moved from the basement to KH 210. Additionally, via oral history, there is some indication that human remains from Rio Vista were removed to Wells Hall. However, beyond oral history, Craig cannot find any documentation regarding this movement even though it was quite recent. Unfortunately, the exact locations and dates for these various changes over time were either not logged in a central place, or in some cases apparently at all, making reconstruction difficult if not impossible. Lack of location control makes it difficult to determine if parts of the collection are missing. By bringing all archaeological materials (and all museum objects) into a formal collections management database, and keeping that database current, the movement history (and conservation condition) of archaeological objects can be far better tracked as each individual relocation stays with the object record as a linked table. Craig was not able to inventory all archaeological materials in Kent Hall, but submitted a proposal to IMLS to undertake that work during the academic year starting in Fall 2024.

References

Footnotes

Both the Murdock and Amador collections are in need of rehabilitation. Through funding from NMSU’s Research Administration Service (RAS), between Fall 2023 and Spring 2024 the UM began rehabilitation of the Amador Collection under Craig’s direction.↩︎

The UM is currently running PastPerfect Network Version 5.0F4.↩︎

Archaeology is a broad subject that encompasses all material culture. Here archaeological is used in the traditional and restricted sense to refer to ancient or historic material culture that is recovered from fieldwork consisting of survey and/or excavation.↩︎